|

This page is about the many materials and methods I offer for making a

personalized book for the client who wants the most special and

ecclectic of personal items. This book is named for the client, who's

last name is Schiff. He wanted a book done in the style of

French/Flemish book arts of the end of the 15th century. The subject

matter is biblical, and you can see some of the major illuminations on

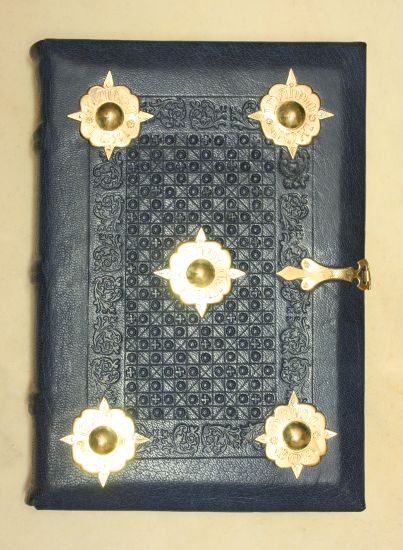

my Illuminated Manuscripts Art Page. The book is 5x7 inches,

Gothic bound in hardwood boards over dark blue goatskin. The pages are

all genuine goat parchment, written in medieval inks and illustrated

with genuine gold & silver leaf, and pigments made from plants,

animals, minerals and chemistry. The binding was hand sewn, carved and

tooled, and features hand-made metal bosses and clasp.

I am also currently writing a book on how to make a medieval book, entitled: Secrets Of Forgotten Masters: A 21st Century Artist's Exploration of how books were made in the Middle Ages. That book will be a comprehensive visual exploration of the materials and techniques used by medieval artists and craftsmen to produce entire books. It will feature sections on tool making, materials collection and manufacture, color making, and binding. Each section will be fully illustrated with photographs. The information will be documented from extant sources and treatises from the medieval period. |

The Schiff Medieval Illuminated Manuscript Book Copyright 2011 Randy Asplund 5x7 inches. Medieval paints, gold and silver leaf, and oak gall ink on goatparchment. Brass hardware over dark blue tooled goat leather. Making Parchment  The

first step in making a medieval book is gathering the pages to write

upon. These were usually made from parchment, and later paper. The

parchment is made from the skins of goats, sheep, and calves. I use

both parchment that I have purchased and parchment that I have made.

Above is a pool of a dozen and a half goat and sheep skins soaking

after being flayed. I am removing the dirt, feces and blood from the

pelts before I process them.

I made a

fleshing knife and this is me scraping the raw flesh from the inside of

a skin. The next stage will be to soak it in a lime water solution for

over a week, then scrape off the hair, and then soak it a second time

in lime water solution.

After

soaking, the skin is stretched on a frame and scraped very smooth with

a crescent shaped knife called a lunelarum. I am pictured here in 14th

c. costume using a reproduction lunelarum. The next step involves

drying, sanding with a block of pumice, and then smoothing the skin

until it is perfect. See the Ecclesiastes article for preparation of

the pages.

The Manuscript  I write

using a goose quill pen and I hold the parchment flat on my 15th c.

type writing slope with my 15th c. type of pen knife. I make these

tools to get a more authentic method in order that my work looks more

correct.

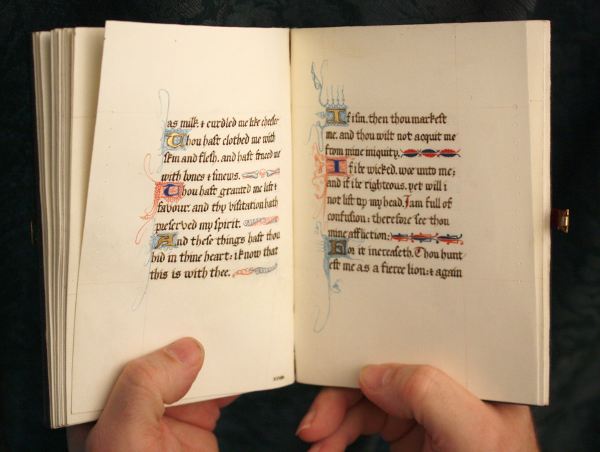

This is

what the finished calligraphy looks like in the Schiff book. There are

fine ink rulings using my home-made brazil wood ink, the dark blue is

coarse ground azurite and the pale blue is fine ground azurite pigment

that I made. The red is vermilion, and the dark brown/bladck ink is oak

gall ink that I made.

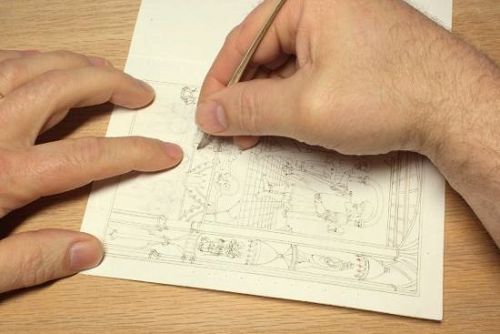

After

the calligraphy comes the illustrating Illustrations are called

Illuminations because the gold brightens the page with light, but it

generally refers to the painting. The design is drawn with

a lead/tin stylus known as a plumet that I made, and it is then inked

with dilute oak gall ink. Then I erase the plumet lines with a wad of

bread. This illustration is the Covenant Between Johnathan and David

full page miniature in the Schiff Book.

The

gilding follows the underdrawing after its contents have been inked. I

make a gesso ground from a red clay called bole, some chalk for a bulk

former, a few drops of honey, and some hide glue. I apply this wherever

the gold will be. After it dries I breathe on it to bring up a tack,

and then lay genuine gold leaf on it. When it is dry enough I burnish

with a burnisher that I made from the tooth of a dog or from another

agate burnisher that I made.

Burnishing with an agate burnisher that I made Making Medieval Paints

These

are justa few of the many colors that I make for my Medieval Manuscript

Illuminated Books. We have verdigris on a copper plate, and next to it

are yellow orpiment, iron oxide, calcined chicken bones, azurite,

yellow ochre, chared bone, vine and wood, red lead, malachite, and

lapis lazuli. I also make pigment from insects, other

minerals and chemicals, and a lot of different plants and even gall

bladders of fish and cows. The colors are made into paint with the

addition of sap from acacia, cherry or plum trees, and I also use the

fluid left after I beat egg whites. The later is called glair.

I

process the petals of cornflowers, irises, violets, poppies, the

berries of buckthorne, elder, and european bilberries and many more

plants to extract vibrant hues. While not lightfast for display in a

frame, they last centuries when used in a book.

Ultramarine was collected only in Afghanistan during the middle ages.

It is mined today as it was back then, with pick axes by hand. From

there it travels by mule and camel, always in danger, and the caravan

must pay off warlords, bandits and pay government taxes before selling

it to the middleman who brings it to New York and whom I buy it from.

In the middle ages it was sold to a Venetian, who shipped it to Europe.

I select only the very best pebbles, but even the deepest blue stones

are loaded with white calcite and pyrite in the matrix. This must all

be removed, so I use the materials above to clean it. Here we have

bee's wax, gum mastic resin, turpentine (sap of the larch), and potash

lye.

The

first step is to mull the lapis lazuli grit as fine as possible on the

slab. Even then, there will be a lot that is not fine enough, so I use

a medieval water levigation method to extract the fine from the coarse,

and then I mull the coarse grit until it is finally all perfect.

The

powder is melted with the wax and resins, kneeded like a putty, and

then put in a bowl of lye and worked with skicks. The blue comes out in

the lye and leaves the impurities in the putty. When the fluid is

poured off, it goes into a hollowed-out non-vitrious brick that pulls

the lye out and leaves only the ultramarine on the surface. The powder

is collected and can be mixed with binder to form paint.

In this

reproduction 15th c. pot I am brewing weld plant tops (aka dyer's weed)

to make a yellow paint called Weld Lake, or in Italy, Arzica. This

beautiful yellow is a dye being extracted with hot potash lye. Then the

dye is stained onto chalk with alum. I collected this weld from the sea

shore in Sweden and I also grow it here in the USA. I washed the sticky

brown soot from the bottom of the pot with more lye and made the

pigment Bistre from it. Bistre is a warm, dark chocolate brown.

This is

sap green being made from buckthorne berries collected from my yard.

The darl purplish blue berry juice becomes a rich green when mixed with

alum in the presence of calcium such as sea shell.

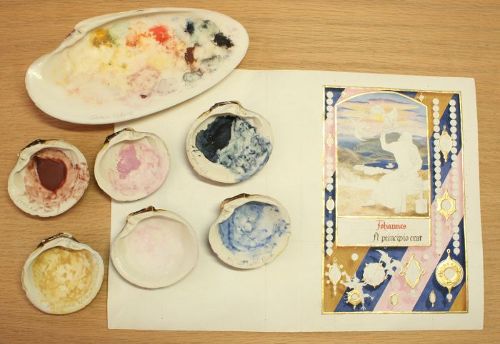

Illuminating The Book  I use

shells as my palettes, just as was done in the middle ages. The colors

are mixed to general hues and values in single shells, and in the

renaissance a large shell or slab of ivory was used for the fine mixing

necessary for naturalistic painting. here are yellow ochre,

cochineal and lapis lazili being used to make the background panels in

the border. They are shaded with red ochre, less tinted cochineal, and

woad. This is the John on the Isle of Patmos full page miniature

from the Schiff book. I even went so far as to find a picture of the

view outside the cave where John wrote the Book of Revelations.

I am

using genuine vermilion over yellow made from buckthorne berries to

make a wreath around an illumination of a skull in a mirror. The image

of death reflected in the mirror (memento mori) was a common medieval

image to remind us that we are all mortal. The flowery script is

decorated with cadel pen work.

The

strawberry on the full page tromp l'oeil illumination of David in his

Penance is laid in with vermilion in this washes, and the green is a

combination of malachite mixed with a brilliant buckthorn yellow. The

yellow ochre background has been stippled with genuine gold paint to

make a shimmering effect.

The image comes to life

as shadow tones are applied, and red ochre seed holes are dotted with

genuine gold paint.

NEXT The Final Illuminations and the Binding |